History of the Bradford-Marcy Cemetery

In 2015 the Woodstock (CT) Historic Properties Commission undertook a project to foster documentation and preservation of historic cemeteries of the Town of Woodstock. A grant from the Connecticut State Historic Preservation Office provided funding to inventory, evaluate, and assess the grave markers in the historic, town-owned Bradford-Marcy Cemetery as a pilot study for inventorying and documenting all of the historic cemeteries in the town. The ultimate goal of the grant was to create this webpage to allow free public access and search capabilities to researchers and the general public to a database of the burials and grave markers in the Bradford-Marcy Cemetery and, in the future, to data on the other historic cemeteries in the Town of Woodstock. (Project consultants included: Raber Associates of South Glastonbury, CT (historical consultants) and Stratos Studio of Woodstock, CT (web site development).

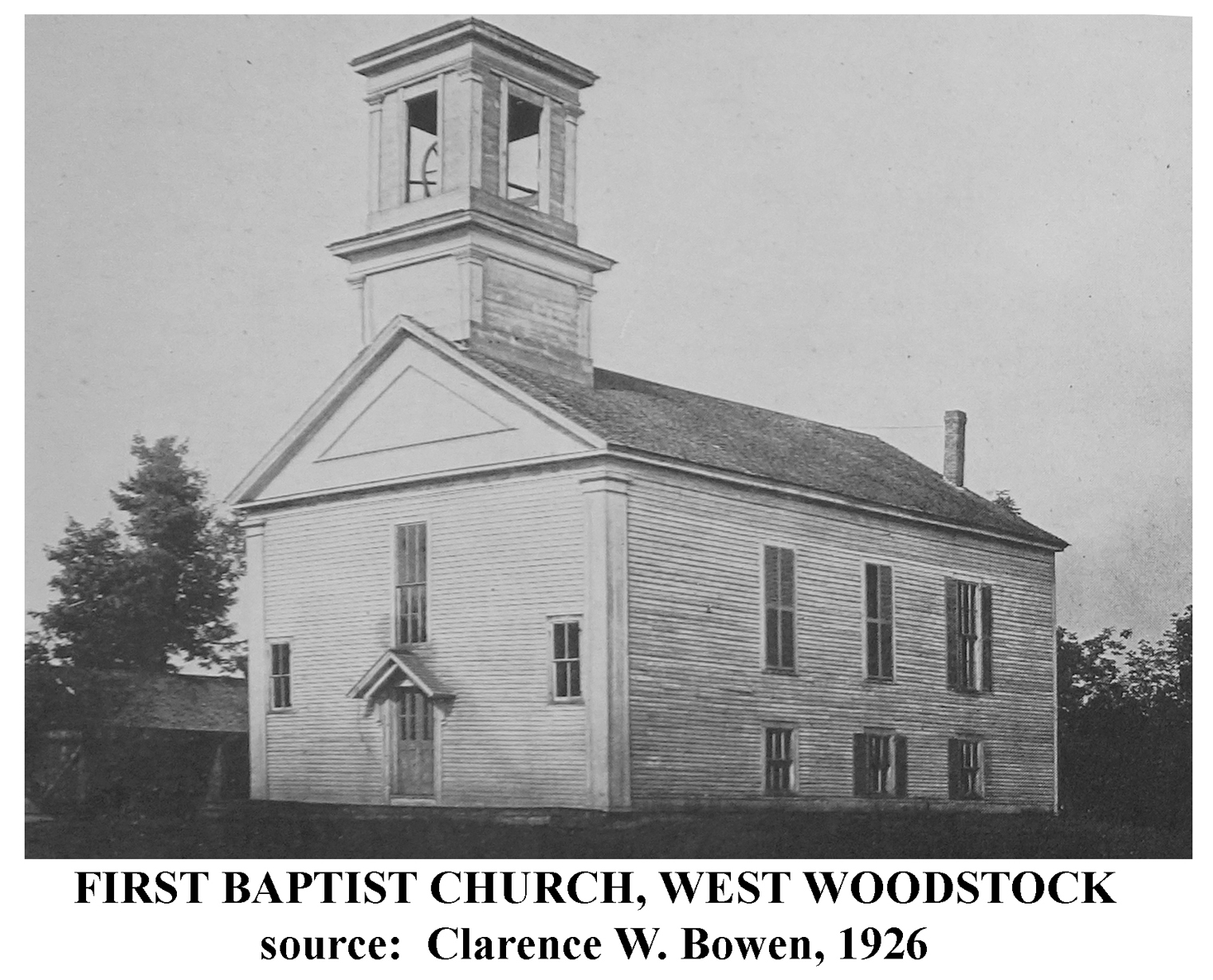

The Bradford-Marcy Cemetery is probably the least documented of the nine public or multi-family Euro-American burial grounds established in present Woodstock, Connecticut, between 1686 and 1906. Although no land records confirm ownership or transfer of the 0.9-acre cemetery parcel on Center Road in the village of West Woodstock before the late 20th century, the cemetery was almost certainly associated with the former First Baptist Church which had a meeting house and a parsonage a short distance away on Bradford Corner Road. Evidence for the connection includes correspondence sent to town selectmen in 2008 and the fact that a number of church deacons and their family members identified in Richard Bayles's 1889 History of Windham County, Connecticut, are buried in the cemetery. The Bradford and Marcy families, many of whom were church members, owned land including or adjacent to the cemetery parcel. Members of the Bradford family supported cemetery development without formal transfer of title to the church; in his 1929 will, Henry M. Bradford left a bequest of $500 to care for the cemetery. It is not known when the cemetery acquired its present name. An 1883 map identifies the lot as the North Cemetery, perhaps in contrast to the South (now known as Barlow) cemetery which had no church affiliation, located about a mile to the southwest.

The Bradford-Marcy Cemetery is probably the least documented of the nine public or multi-family Euro-American burial grounds established in present Woodstock, Connecticut, between 1686 and 1906. Although no land records confirm ownership or transfer of the 0.9-acre cemetery parcel on Center Road in the village of West Woodstock before the late 20th century, the cemetery was almost certainly associated with the former First Baptist Church which had a meeting house and a parsonage a short distance away on Bradford Corner Road. Evidence for the connection includes correspondence sent to town selectmen in 2008 and the fact that a number of church deacons and their family members identified in Richard Bayles's 1889 History of Windham County, Connecticut, are buried in the cemetery. The Bradford and Marcy families, many of whom were church members, owned land including or adjacent to the cemetery parcel. Members of the Bradford family supported cemetery development without formal transfer of title to the church; in his 1929 will, Henry M. Bradford left a bequest of $500 to care for the cemetery. It is not known when the cemetery acquired its present name. An 1883 map identifies the lot as the North Cemetery, perhaps in contrast to the South (now known as Barlow) cemetery which had no church affiliation, located about a mile to the southwest.

The First Baptist Church was organized in 1766 and grew somewhat erratically into the first quarter of the 19th century in an era of religious turmoil. Membership reached 110 in 1825 and climbed to nearly 200 by the early 1840s. A new meeting house was built in 1806 and a parsonage (rebuilt circa 1870) was first constructed across Bradford Corner Road around 1815. The cemetery was likely opened in response to the church’s growth. First referred to as a burying ground in an 1816 deed for an adjacent parcel, the cemetery was in use by 1809 when three small children were interred. Cemetery inscription data assembled in the 1930s indicate approximately 293 more people were buried here during the 19th century. West Woodstock lost much of its population in the two decades after the Civil War, as local industries closed in the face of floods, fires, and poor rail connections; and by the end of the 19th century, the First Baptist Church and a number of other congregations in Woodstock were in decline. The First Baptist Church disbanded at an unknown date in the early 20th century, a fact perhaps reflected by the burial of only twenty-four people at the cemetery between 1900 and 1935. The meeting house and parsonage have since been removed.

The First Baptist Church was organized in 1766 and grew somewhat erratically into the first quarter of the 19th century in an era of religious turmoil. Membership reached 110 in 1825 and climbed to nearly 200 by the early 1840s. A new meeting house was built in 1806 and a parsonage (rebuilt circa 1870) was first constructed across Bradford Corner Road around 1815. The cemetery was likely opened in response to the church’s growth. First referred to as a burying ground in an 1816 deed for an adjacent parcel, the cemetery was in use by 1809 when three small children were interred. Cemetery inscription data assembled in the 1930s indicate approximately 293 more people were buried here during the 19th century. West Woodstock lost much of its population in the two decades after the Civil War, as local industries closed in the face of floods, fires, and poor rail connections; and by the end of the 19th century, the First Baptist Church and a number of other congregations in Woodstock were in decline. The First Baptist Church disbanded at an unknown date in the early 20th century, a fact perhaps reflected by the burial of only twenty-four people at the cemetery between 1900 and 1935. The meeting house and parsonage have since been removed.

Like most of Woodstock’s other church-associated cemeteries after the early 1920s, Bradford-Marcy Cemetery management was transferred to a corporation run by people with personal connections to the burials. Established in 1935, Bradford-Marcy Cemetery, Inc., maintained the grounds with only two additional burials until a gradual decline in the number of relatives of decedents made further private management very difficult. The last corporate officer died in 1973 and in 1975 the Town of Woodstock established the Bradford-Marcy Cemetery Committee to continue maintenance with remaining corporation funds. A small permanent trust fund for maintenance was established in 1989 under the will of Richard C. Noren, who had been involved with the corporation and became the cemetery’s last decedent.

The cemetery reflects the transition in attitudes towards death and burial among Euro-American New Englanders after the late 18th century. Until that period, death was regarded as a divinely-ordained fate common to all, and the terms “burying grounds” or “graveyards” designating places of burial to indicate less emphasis on eternity than on finality, with graves oriented east-west and commonly marked with fieldstones (unmarked, unfinished stones) and carved tablet-style headstones. As death for Christian Euro-Americans became viewed as more of a reward and a beginning of eternal life, a “cemetery” (from the Greek κοιμητήριον: sleeping place) denoted a place of rest and was often a planned landscape. The relatively small Bradford-Marcy Cemetery was established south of a wetland, on a low hill with steep slopes on the east side and northeast corner. Assuming the headstones are largely in original positions, the earliest graves indicate the central 12-foot-wide corridor between the east and west cemetery sections was planned from initial cemetery use. Graves are oriented north-south, with many originally having a headstone and footstone markers. All of the approximately 125 surviving footstones appear to have been moved to accommodate grass-mowing equipment. Most of the earliest graves are on the highest ground near the central corridor, with later burials arranged in rows on either side of the corridor. There are no enclosed family groupings, but markers for many of the approximately fifty families represented in the cemetery are arrayed in adjacent positions in one or more rows. Markers for the Bradford and Marcy families occupy prominent places at the south or front side of the cemetery, anchored by some of the large markers noted below. At an unknown date, a stone wall of dry-laid rubble and slabs was built around the perimeter of the cemetery, with two gated openings on the south side near Center Road: a central 8-foot-wide pedestrian stepped entry and an approximately 9-foot-wide vehicular entry at the east end leading to a lane below the graves for transport of coffins and grave marker materials.

Until the second half of the 19th century, all of the principal grave markers were tablet-style headstones with several types of upper surface styles. Of the earliest twenty-six tablets installed by 1821, at least fifteen were schist and nine were slate. These were local materials, and the schist markers may have come from a quarry in Bolton, Connecticut, used by stone carvers and quarry owners named Loomis. After the early 1820s, the remaining approximately 208 tablet markers were all made of marble and granite, probably from quarries in nearby areas of Massachusetts as suggested by limited marker information on carvers from Webster and Worcester. Most tablet inscriptions, were still legible, focus on going to heaven as a reward and on regrets for those left behind. From the 1850s to perhaps the 1890s, twenty-one larger granite and marble markers were installed by nine families, including seven pedestals, ten large oblong monuments, and four obelisks. The larger markers generally memorialize multiple members of one family or sometimes show just the family name with individual markers arranged nearby. Commonly inspired by Egyptian Revival associations with eternal life, the obelisks and pedestals became symbols for Christian belief in the eternity of the spirit. In many New England cemeteries, obelisks and pedestals appear in the second quarter of the 19th century.

CLICK HERE TO SEARCH CEMETERY DATABASE

REFERENCES

Bayles, Richard M.

1889 History of Windham County, Connecticut. New York: W.W. Preston & Co.

Bowen, Clarence W.

1926 The History of Woodstock, Connecticut, Vol. 1. Norwood, MA: Plimpton Press.

Farber, Jessie L.

2010 Symbolism on Gravestones. The Association for Gravestone Studies. Available on World Wide Web at http://www.gravestonestudies.org

Gerrish, E. P., and others

1856 Windham County, Connecticut, From Actual Survey. Philadelphia: Woodford and Bartlett.

Gray, O.W.

1869 Atlas of Windham and Tolland Counties... Hartford: D.G. Keeney.

Hale, Charles R.

c1932-35 Hale Collection of Connecticut Cemetery Inscriptions. Funded by U.S. Works Projects Administration. Connecticut State Library.

Available on World Wide Web at http://www.familysearch.org

Larned, Ellen D.

1880 History of Windham County, Connecticut. Vol. 2. Worcester, MA: Charles Hamilton.

LaChapelle, Elaine

2016 Woodstock’s History Detective Presents the Case of the Elusive Cemeteries. Powerpoint presentation.

Lester, John S.

1883 Map of Woodstock, Conn. Annotated 1886 by George C. Williams. Included in Bowen 1926.

Potter, Elisabeth W., and Beth M. Bolan

1992 Guidelines for Evaluating and Registering Cemeteries and Burial Places. National Register Bulletin 41. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service.

Town of Woodstock, Connecticut

n.d. Office of the Woodstock Town Clerk: Manuscript Land and Probate Records; Will of Henry M. Bradford, Probate Records Vol. 18. pp. 564-566, 1929; Bradford-Marcy Cemetery file.

Woodstock Historical Society

n.d. Folder: Bradford-Marcy Cemetery Correspondence, 1940-1998.

The Town of Woodstock received funds for this project from the Department of Economic and Community Development State Historic Preservation Office with federal funds from the Historic Preservation Fund of the National Park Service, US Dept. of the Interior. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department or the Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department or the Department of the Interior.

This program receives Federal financial assistance through the Department for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, sex, national origin, or handicap in its federally assisted programs. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility described above, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, U.S. National Park Service, 1849 C Street, NW, Washington, DC 20240